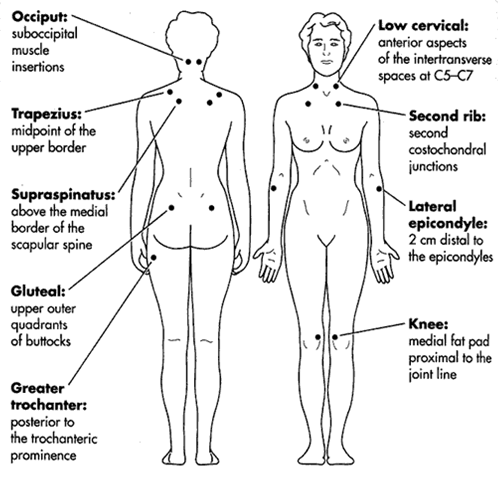

General Trigger Points

Fibromyalgia Trigger Points (Posterior, Anterior and Lateral/Side)

TRIGGER POINT HISTORY, THEORY, PHYSIOLOGY & ANATOMY

Online 12 hour CEU Approved by The Texas Massage Therapists Board

Texas DSHS Licensed Online CEU Provider CE 1608 Dan C. PhD EMT LMT MTI Granbury, TX

TAKE EXAM" or Email minimum 3 page report on the Trigger Point Study Material you have reviewed to "info@cleanwater4.us" for the 12 hour CEU Certificate

VIDEOS

|

Sternocleidomastoid Trigger Points and Referred Pain Patterns |

Watch this Introductory Slide Show Trigger Point Theory Slide Show | Trigger Point Theory Slide Show Alternate

Introduction to Anatomy & Physiology | Body Organization | Body Systems | Functions/Divisions of Nervous System | Central Nervous System

Simple Explanations/Introductions to Trigger Point

Trigger points are places in the body where muscles do not function properly because they have been damaged on the cellular level. Not everybody who sprains a tendon or pulls a muscle will develop a trigger point, but those that do know that they are a source of constant chronic pain (16).

Definition of a Trigger Point

A trigger point appears as a hard tender lump in the body of a muscle. It can be as small as a pin point or as big as a thumb. It is highly sensitive to pressure. A trigger point will have intense contractile activity without any sort of nerve stimulation. It is described as being similar to a muscle cramp, but in a very small circular area.

Trigger Point Anatomy

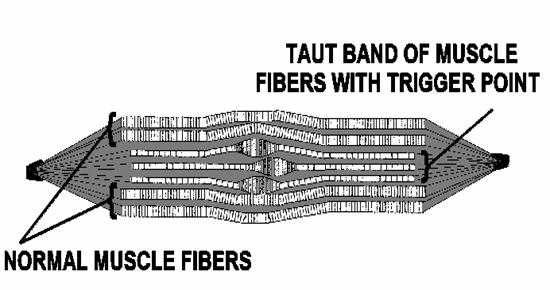

A band of muscle that has a trigger point will have normal muscle fibers and a taut band of muscle fibers, which bunch up in a knot and cause stretching and elongation of muscle fibers to either side of the trigger point. The muscle fibers that are stretched like this have severe damage at molecular and sub-cellular levels because of the intense contractile activity in the trigger point area.

Failure to Reabsorb Calcium

When a muscle contracts, calcium is released into the muscle. In a resting muscle cell the co-enzyme ATP, which is responsible for energy transfer between cells, is bound to myosin, a motor protein. The myosin has to wait for calcium to be released by the cells before it can contract or release a fiber of muscle. Normal muscles have enough ATP in their cells and can reabsorb the calcium and effectively stop muscle contraction. A trigger point zone in the muscle cannot reabsorb the calcium to turn a contraction off. The contraction continues to occur and this causes a build up of lactic acid, which leads to molecular damage of the muscle fibers.

Pioneers in Trigger Point History

Dr. Janet Travell�s personal success with one particular patient had a far-reaching effect on history (4). Not many people remember that Janet Travell was the White House Physician during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. President Kennedy honored her with that position in gratitude for her treatment of the debilitating myofascial pain and certain other ailments that in 1955 had threatened to prematurely end his political career. It�s a stunning example of how trigger point therapy can change someone�s life and destiny.

Although in her sixties at the end of her duties at the White House, Dr. Travell had no intention of retiring or even slowing down. She went on developing and teaching her methods with vigor and enthusiasm for the next thirty years. She was past eighty when the first volume of her grand opus, Myofascial Pain & Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual was published, and past ninety when the second volume appeared. She refused to rush into print: she wanted to get it right.

Janet G. Travell, MD (1901-1997) and David G. Simons, MD (1922-) first met when Dr. Travell lectured about trigger points and myofascial pain at the Air Force�s School of Aerospace Medicine. Dr. Simons was so intrigued by Dr. Travell�s work that he eventually retired from the Air Force and began a long informal apprenticeship under her wing.

David Simons (4) lends authority to the study of myofascial pain with his long experience as a research scientist. In his early career, Dr. Simons worked as an aerospace physician, developing improved methods of measuring physiological responses to the stress of weightlessness.

A fascinating sidelight to Dr. Simons�s career is the world altitude record for manned balloon flight he set in 1957 as a young Air Force Flight Surgeon. In point of fact, he beat Sputnik into space. He was featured on the cover of Life magazine that year and subsequently wrote a book, Man High, about his adventure.

Dr. Simons�s strict attention to detail and adherence to scientific method helped him bring rigorous objectivity to the documentation of myofascial pain. He was the driving force in getting the Travell and Simons books written, doing most of the actual writing himself, with Dr. Travell�s vast knowledge and experience as his primary resource. One day, when ordinary people know about trigger points and the diagnosis and treatment of myofascial pain is taught widely in medical schools, physicians everywhere will honor Doctor Simons, along with his mentor, Dr. Travell, as true medical pioneers.

Into his eighties now, David Simons is still hard at work promoting further research concerning trigger points. His latest book, Muscle Pain: Understanding its Nature, Diagnosis, and Treatment, with coauthor Doctor Siegfried Mense, seeks to impart a better understanding of the neurophysiology of muscles (4).

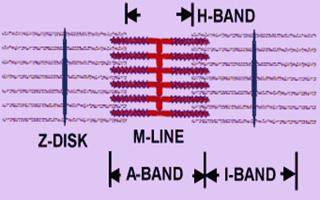

Muscle Fibers with a microscopic view, Trigger Points and their Physiology

The part of a muscle fiber that actually does the contracting is a microscopic unit called a sarcomere (4). Contraction occurs in a sarcomere when its two parts come together and interlock like fingers.

Millions of sarcomeres have to contract in your muscles to make even the smallest movement. A trigger point exists when over stimulated sarcomeres are chemically prevented from releasing from their interlocked state.

The

drawing is a representation of several muscle fibers within a trigger point.

It�s based on a microscopic photograph of an actual trigger point.

The

drawing is a representation of several muscle fibers within a trigger point.

It�s based on a microscopic photograph of an actual trigger point.

This particular trigger point would cause a headache over your left eye and sometimes at the very top of your head.

Letter A is a muscle fiber in a normal resting state, neither stretched nor contracted. The distance between the short crossways lines (Z bands) within the fiber defines the length of the individual sarcomeres. The sarcomeres run lengthwise in the fiber, perpendicular to the Z bands.

Letter B is a knot in a muscle fiber consisting of a mass of sarcomeres in the state of maximum continuous contraction that characterizes a trigger point. The bulbous appearance of the contraction knot indicates how that segment of the muscle fiber has drawn up and become shorter and wider. The Z bands have been drawn much closer together.

Letter C is the part of the muscle fiber that extends from the contraction knot to the muscle�s attachment (to the breastbone in this case). Note the greater distance between the Z bands, which displays how the muscle fiber is being stretched by tension within the contraction knot. These overstretched segments of muscle fiber are what cause shortness and tightness in a muscle.

Normally, when a muscle is working, its sarcomeres act like tiny pumps, contracting and relaxing to circulate blood through the capillaries that supply their metabolic needs. When sarcomeres in a trigger point hold their contraction, blood flow essentially stops in the immediate area.

The resulting oxygen starvation and accumulation of the waste products of metabolism irritates the trigger point. The trigger point responds to this emergency by sending out pain signals.

These pain signals will continue unless trigger points are located, deactivated, and the associated tissue flushed to help the trigger point�s contracted sarcomeres begin to release.

Referred Pain, Trigger Points and Myofascial Pain

The defining symptom of a trigger point is referred pain; that is, trigger points usually send their pain to some other site. This is an extremely misleading phenomenon and is the reason conventional treatments for pain so often fail. It�s a mistake to assume that the problem is at the place that hurts!

Referred pain is felt most often as an oppressive deep ache, although movement can sharpen the pain. Referred myofascial pain can be as intense and intolerable as pain from any other cause, including surgery. Myofascial pain can do a very good job of mimicking a heart attack.

Some common examples of referred pain are headaches, sinus pain, and the kind of pain in the neck that won�t let you turn your head. Jaw pain, earache, and sore throat can also be expressions of referred pain. Another is the incapacitating stitch in the side that comes from running too hard.

Aching legs, sore feet, and sprained ankles are other examples of referred pain. Stiffness and pain in a joint should always make you think first of possible trigger points in nearby muscles that have been subjected to strain or overwork.

Pain in such joints as the knuckles, wrists, elbows, shoulders, knees, and hips are almost always nothing more serious than referred pain from myofascial trigger points.

The easiest theory to accept regarding referred pain is that the signals simply get mixed in your neurological wiring. Sensory inputs from several sources are known to converge into single neurons (nerve cells) at the spinal level, where they are integrated and modified before being transmitted to the brain.

Under these circumstances, it may be possible for one electrical signal to influence another, resulting in mistaken impressions about where the signals are coming from (4).

Headache, Toothache, Sinus Pain, TMJ, Ear Itch

The

illustration shows trigger points in a jaw muscle (masseter) that can cause a

frontal headache and pain in the sinuses, teeth, ears and temporomandibular

joints (TMJ disorder). They can be responsible for a sense of sinus pressure or

congestion. These trigger points are also the cause of that familiar maddening

itch deep inside the ear.

The

illustration shows trigger points in a jaw muscle (masseter) that can cause a

frontal headache and pain in the sinuses, teeth, ears and temporomandibular

joints (TMJ disorder). They can be responsible for a sense of sinus pressure or

congestion. These trigger points are also the cause of that familiar maddening

itch deep inside the ear.

Tennis Elbow, Elbow Tendinitis

The

illustration shows trigger points in the extensor carpi radialis longus muscle.

These are the most common cause of pain in the outer elbow, commonly called

tennis elbow, elbow tendinitis, or lateral epicondylitis. Trigger points in

other forearm muscles cause numbness, tingling, burning, swelling, weakness and

stiffness in the wrists, hands and fingers:

The

illustration shows trigger points in the extensor carpi radialis longus muscle.

These are the most common cause of pain in the outer elbow, commonly called

tennis elbow, elbow tendinitis, or lateral epicondylitis. Trigger points in

other forearm muscles cause numbness, tingling, burning, swelling, weakness and

stiffness in the wrists, hands and fingers:

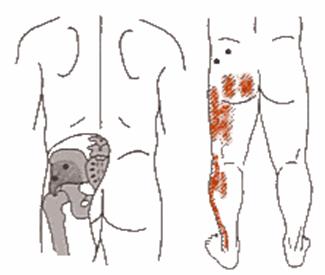

Low Back Pain

The

reason there are so many differing opinions about the cause of back pain is

that it's mostly referred pain. You may never find back pain's real cause if

you look for it only in the back muscles or the spine. back pain very often comes

from trigger points in stomach muscles, for instance. The illustration shows a

gluteus medius trigger point that is one of the most common causes of low back

pain:

The

reason there are so many differing opinions about the cause of back pain is

that it's mostly referred pain. You may never find back pain's real cause if

you look for it only in the back muscles or the spine. back pain very often comes

from trigger points in stomach muscles, for instance. The illustration shows a

gluteus medius trigger point that is one of the most common causes of low back

pain:

Ankle Pain

You may not have

ever thought about it, but the muscles of the lower leg are actually foot

muscles. It should be no surprise that much of the pain in the feet and ankles

comes from lower leg muscles. The illustration shows the trigger point in the

side of the lower leg that causes pain in the ankle that feels just like a sprain.

You may not have

ever thought about it, but the muscles of the lower leg are actually foot

muscles. It should be no surprise that much of the pain in the feet and ankles

comes from lower leg muscles. The illustration shows the trigger point in the

side of the lower leg that causes pain in the ankle that feels just like a sprain.

Research has shown that trigger points are the primary cause of pain 75% of the time and are at least a part of nearly every pain problem.

Trigger points cause headaches, neck and jaw pain, low back pain, tennis elbow, and carpal tunnel syndrome. They are the source of the pain in such joints as the shoulder, wrist, hip, knee, and ankle that is so often mistaken for arthritis, tendinitis, bursitis, or ligament injury.

Trigger points also cause symptoms as diverse as dizziness, earaches, sinusitis, nausea, heartburn, false heart pain, heart arrhythmia, genital pain, and numbness in the hands and feet. Even fibromyalgia may have its beginnings with myofascial trigger points.

Patients with chronic myofascial pain are people who have suffered more than just pain for many months or longer (15). The severity and chronicity of their "untreatable" pain has often reduced their physical activity, limited participation in social activities, impaired sleep, induced a major or minor degree of depression, caused loss of role in the family, led to loss of employment, and deprived them of control of their lives. Many have been depersonalized by the ultimate indignity-the conviction that their pain is not "real," but psychogenic. Well-meaning practitioners sometimes have also convinced the patients' families and friends that the pain is not real, leaving many patients nowhere to turn for help. The patients come to the clinician seeking relief from their suffering, which they may present only in terms of pain

Many people suffer from sensitive spots in muscle, often called trigger points or muscle knots.� Trigger points may be more clinically important than most health professionals realize, and body pain seems to be a growing problem.� It may be more literally true than you realized! Some evidence shows that a knot may be a patch of polluted tissue: a nasty little cesspool of waste metabolites. If so, it�s no wonder they hurt, and no wonder they cause so many strange sensations: it�s more like being poisoned than being injured. Back pain is the best known symptom of the common muscle knot, but they can cause an astonishing array of other aches and pains, and misdiagnosis is the rule (14).

Trigger points are referred to erroneously as the sore spot in the muscle where the referred pain is felt which is usually not the source of the problem.� The underlying problem causing the referred pain is actually in a different location because the source of the pain is in a location different from the location of the referred pain felt by the body.

Myofascial Trigger Points

A myofascial trigger point is defined as "a hyperirritable spot, usually within a taut band of skeletal muscle or in the muscle fascia, that is painful on compression and that can give rise to characteristic referred pain, tendereness, and autonomic phenomena"(2)

Myofascial TrPs may be perpetuated by mechanical (structural or postural) factors, by systemic factors, by associated medical conditions, and by psychological stress. �The central nervous system powerfully modulates pain input from the muscles in ways that can explain referred pain and altered sensation from TrPs. In phase 1 (constant pain from severely active TrPs), patients may already have such intense pain that they do not perceive an increase and cannot distinguish what makes it worse. Phase 2 (pain from less irritable TrPs that is perceived only on movement and not at rest) is ideal for educating the patient as to which muscles and movements are responsible for the pain, and how to manage it. In phase 3 (latent TrPs that are causing no pain), the patient still has some residual dysfunction and is vulnerable to reactivation of the latent TrPs.

What exactly are muscle knots?

When you say that you have �muscle knots,� you are talking about myofascial trigger points (14).� There are no actual knots involved, of course. Although their true nature is uncertain, the dominant theory is that a trigger point (TrP) is a small patch of tightly contracted muscle, an isolated spasm affecting just a small patch of muscle tissue (not a whole muscle spasm like a �charlie horse� or cramp). That small patch of knotted muscle cuts off its own blood supply, which irritates it even more � a vicious cycle called �metabolic crisis.� The swampy metabolic situation is why I sometimes also call it �sick muscle syndrome.�A collection of too many nasty trigger points is called myofascial pain syndrome (MPS).

Trigger Points in Chronic Pain

Individual TrPs and MPS can cause a shocking amount of discomfort �far more than most people believe is possible, as well as some surprising side effects. Its bark is much louder than its bite, but the bark can be extremely loud (14).

Trigger Points can:

1. cause pain problems,

2. complicate pain problems, and

3. mimic other pain problems.

Trigger points can cause pain directly.

Trigger points are a �natural� part of muscle tissue.� Just as� almost everyone gets some pimples, sooner or later almost everyone gets muscle knots, and you have pain with no other explanation.

Trigger points complicate injuries.

Trigger points show up in most painful situations like party crashers.� Almost no matter what happens to you, you can count� on trigger points to make it worse. In many cases they� actually begin to overshadow the original problem.

Trigger points mimic other problems.

Many� trigger points feel like something else. It is easy for an� unsuspecting health professional to mistake trigger point pain for practically anything but a trigger point.� For instance, muscle pain is probably more common� than repetitive strain injuries (RSIs), because many so called RSIs may actually be muscle pain

The table below presents the results of some chronic pain investigations.

Table 1: Prevalence of Trigger Points in Patients with Pain Complaints(2)

|

Investigation |

Frequency of Myofascial Pain (trigger point induced pain) as the primary diagnosis. |

|

283 consecutive admissions at a comprehensive pain center. |

85% |

|

296 patients referred to dental clinic for chronic head and neck pain of at least 6 months duration. |

55% (21% had a priomary diagnosis of disease of the temporomandibular joint). |

|

61 consecutive patients at an internal medicine group practice for all causes |

10% (31% of those presenting with a pain complaint) |

Trigger Point Characteristics

Bruce Thomson Details the Anatomical Characteristics of Trigger Points (1) as follows with some interesting diagrams which provide additional detail:-

- The trigger point is a hard, tender "lump" in the body of a muscle. It may be as small as a pinpoint or as big as your thumb, and is exquisitely tender to pressure from finger or thumb or tennis ball.

- The trigger point is characterized by intense contractile activity in the absence of nerve excitation. (Like a muscle with a cramp, but in a small circumscribed area).

- The trigger point is not an inflamed area of muscle; very few microscopic investigations of trigger points reveal the presence of inflammatory cells(1). However, severe damage at the Sub-cellular and molecular levels has been noted, and will be now be discussed.

Trigger

Point Diagram 1: A Trigger Point in a Muscle (2)

Note the bunching up of the muscle fibers in the trigger point knot, and the

stretching and elongation of the muscle fibers to either side of the trigger

point.

Trigger Pt Micro-anatomy: Severe damage at Sub-cellular & Molecular

Levels (2)

|

1. Empty Sarcolemmal tubes where the muscle fiber either side of the trigger point zone has been torn (see diagram 1 above). 2. Torn Actin fibers: microsocpic examination of trigger point sarcomeres reveals signs of damage to actin fibers, ("moth eaten" I bands - that is, torn actin strands close the Z-disk - see diagram 2). |

|

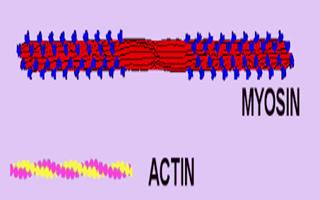

Trigger Point Diagram 2: The Sarcomere - Molecular unit of Muscle Contraction. Intense contractile activity in the area of a trigger point results in tearing of the actin molecules in the region of the Z-disk (adapted from Michael W. King: Muscle Biochemistry - ref. 11).

|

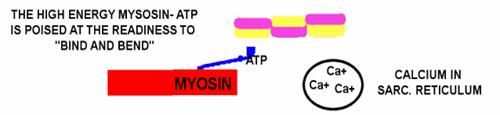

Trigger

Point Biochemistry: The Calcium Switch that Fails to turn off (1).

Muscles contract when, in response to a motor nerve signal, Calcium is released

from storage in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The next two diagrams and captions

discuss this.

Trigger Point Diagram 4: Resting Muscle: In the resting muscle, ATP is bound to Myosin in a

high energy configuration. The Myosin cannot however do anything until Calcium

is released from the sarcoplsamic reticulum. The Calcium switch is turned off.

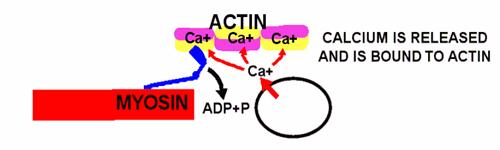

Trigger Point Diagram 5: Muscle in Rigor Mortis - the actin-myosin unit is

locked together and cannot release: The Calcium switch has turned on, and

has enabled the high energy Myosin-ATP to "bind and bend" to the Actin

with the release of low energy ADP and Phosphate. However that is as far as it

goes: there is no more energy currency (ATP) in the muscle cell to drive the

Myosin cycle of "release and straighten, bind and bend", and the

Myosin remains stuck fast to the actin molecule.

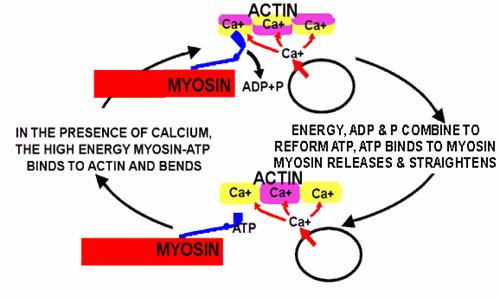

Muscle with Trigger Point Dysfunction (1):

Trigger Point Diagram 6: Active Muscle - In this active muscle, both

Calcium and ATP are present, and the Myosin cycle of "Release and

straighten, bind and bend" is in full flight. The myosin is "walking

up the actin". Normal muscle has sufficient ATP in the cell and sufficient

integrity in its sarcoplasmic reticulum to quickly re-absorb the Calcium and

turn off the contraction. However, a trigger point zone in a muscle cannot

re-absorb the Calcium and turn the contraction off: The contraction continues

until tension pulls hard enough against the Myosin "leg" to stop it

at the bending phase of its cycle. Small wonder that there is intense activity

with build up of lactic acid and molecular damage.

Clinical Application: Why Can't Calcium

Switch in Trigger Point Zones turn off?

This is no idle question. If we knew why the Calcium switch fails to turn off,

we could potentially develop better therapeutic strategies. Here are some

suggestions, alongside therapeutic implications:-

- Mechanical stress to the Sarcoplasmic reticulum: Bunching of the sarcoplasmic reticulum may break its structural integrity -

Stretching, or even resting a muscle at a slightly longer length may enhance sufficient Calcium switch integrity to let it turn off. Likewise avoidance of unnecessary prolonged pressure, for example the "fat wallet" in the back pocket (a common cause of trigger point mediated buttock pain).

- Depletion of Cellular energy and build up of Lactic Acid: Bunching of muscle tissue at the trigger point zone severely disables blood flow, and this, alongside the energy intensive Actin-Myosin activity reduces the cellular energy (ATP) available to the Calcium switch. It also increases local levels of lactic acid, which can be detrimental to cellular function -

Massage, or any gently continuous movement is likely to encourage better blood supply and therefore more available energy at the cellular level, also dietary Minerals, B group vitamins and malic acid may enhance cellular energy metabolism. Also, a reduction in carbohydrates (who's metabolism requires large quantities of B group vitamins) may benefit.

- Poor membrane integrity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum due to "toxic" (hydrogenated and heavily oxidised polyunsaturate) fats: Leads to a poorly functional and easily damaged Calcium switch -

Replace these types of fats with healthy ones in the diet, and increase the dietary anti-oxidants.

- Statins: Disrupt the production of Co-enzyme Q-10, and also the normal and natural membrane component "Cholesterol" -

Muscle pain and/or weakness is one of the many side effects of Statins. If you have these symptoms, consider discontinuing the drug class "Statins", because they destroy Co-enzyme Q-10, which is a very important lipid based anti-oxidant, and because they inhibit the manufacture of the (highly necessary and completely normal) cholesterol component of sarcoplasmic reticulum membranes.

More information, trigger point precipitating factors, see "Trigger Point Diagram Cascade for Diagnosis and Management" (13).

Trigger Points: Referred Pain

|

Active trigger points (1) have more than just a local effect. The worst pain from trigger points may be experienced at the site of the trigger point, but surprisingly often, the pain is "sent" to some point in the musculo-tendinous unit above, below or even to the side of the trigger point. Many trigger points send their pain even further! - The Gluteus minimus is a case in point. The pain is sent via local nerves and central nervous system from the irritated trigger points to the targeted tissues (see diagram). This pattern of referred pain, while not identical between individuals, is remarkably consistent across the human species. |

|

Diagram 1: Trigger Points in the Gluteus minimus and

their combined pain referral patterns. Picture

source: clair Davies, The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook |

|

|

||

Trigger Points: Sentinels for Mechanical Stress So

why do trigger points exist? (1)

Trigger points are ubiquitous in both man and animal. Both their locations in muscles and their patterns of transferred pain/inflammation are remarkably similar between individuals. Such uniformity suggests that both the trigger points and their patterns of referral are strongly encoded at the genetic level; that they are in fact there for a purpose. What can that purpose be?

|

The most likely explanation runs thus:- "Trigger points are sentinels for mechanical stress that warn the organism to guard the likely associated parts, and at the same time initiate a cycle of acute inflammation that is followed by healing and strengthening of likely associated parts". For example, the Gluteus minimus (diagram right) is a "side strut" for the leg. If a trigger point in the Gluteus minimus senses that it is being over-loaded, it is entirely appropriate for it to send a message to all of the "side-strut" muscles and ligaments down the entire length of the leg to warn them to also strengthen up. |

|

|

Trigger points become active subsequent to the following mechanical stressors:-

- Prolonged and/or heavy exertion.

- Mechanical irritation such as the prolonged pressure caused by sitting on a wallet.

- Trauma, either from a direct blow or from "pulling" a muscle.

All the above are examples of mechanical stress. In each situation, trigger points initiate an integrated process designed to limit further damage and to bring about healing and strengthening, thus:-

Initiation of the Guarding Response:

Tissues both near and far are "triggered" to send out pain warnings

that encourage the organism to take it easy, to not put too much pressure on

the damaged part or parts, to perhaps learn a wiser movement pattern.

Final Note Re: Inflammation at the Trigger Point Zone

�

An Injection of "aspirin like" anti-inflammatory (Diclofenac) into a

trigger point relieves pain more strongly than an injection of local anesthetic

(2). So there is good evidence for prostaglandin release at the trigger point

zone. Evidence for other inflammatory or nerve pain substances (substance P,

Leukotrienes, Histamine, Serotonin) at the trigger point site is more

controversial. These substances, together with signs of microscopic

inflammation are however to be found at zones of neurogenic inflammation.

Fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndrome

Fibromyalgia (FM) and myofascial pain syndrome may be two sides of the same painful coin, or at either end of a graph of sensory malfunction. This is an ongoing debate. The two concepts do have a lot in common, routinely coexist, and they are often and understandably confused. Fibromyalgia may be a more clearly neurological disease, while MPS may be more of a dysfunction of muscle tissue (14).

Trigger points also explain many severe and strange aches and pains

This is where trigger points really get interesting. In addition to minor aches and pains, muscle pain often causes unusual symptoms in strange locations. For instance, many people diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome are actually experiencing pain caused by a

muscle in their armpit (subscapularis).

This odd phenomenon of pain spreading from a trigger point to another location is called �referred pain.� Here are some other examples of interesting referred

pain:

Sciatica (shooting pain in the buttocks and legs) is often caused by pain in the piriformis or other gluteal muscles, and not by irritation of the sciatic nerve. Many other trigger points are mistaken for �some kind of nerve problem.�

Earaches, sinusitis, toothaches, ringing in the ears (tinnitus), and dizziness may be symptoms of trigger points in the muscles around the jaw, face, head and neck.

A sore throat or a lump in the throat is often caused or aggravated by trigger points anywhere around the throat.

�Appendicitis pain� often turns out, sometimes after surgery, to be caused by a

trigger point in the abdominal muscles.

Severe MPS is often mistaken for fibromyalgia (and other diseases that cause

hypersensitivity to pain throughout the body).

Sometimes trigger points cause such severe symptoms that they are mistaken for medical emergencies. A physician who had this experience indicated narrowly escaping a breast biopsy because of trigger points in the pectoralis major. �Another client once spent three days in hospital for severe abdominal pain which was actually due to a trigger point in her psoas major muscle.

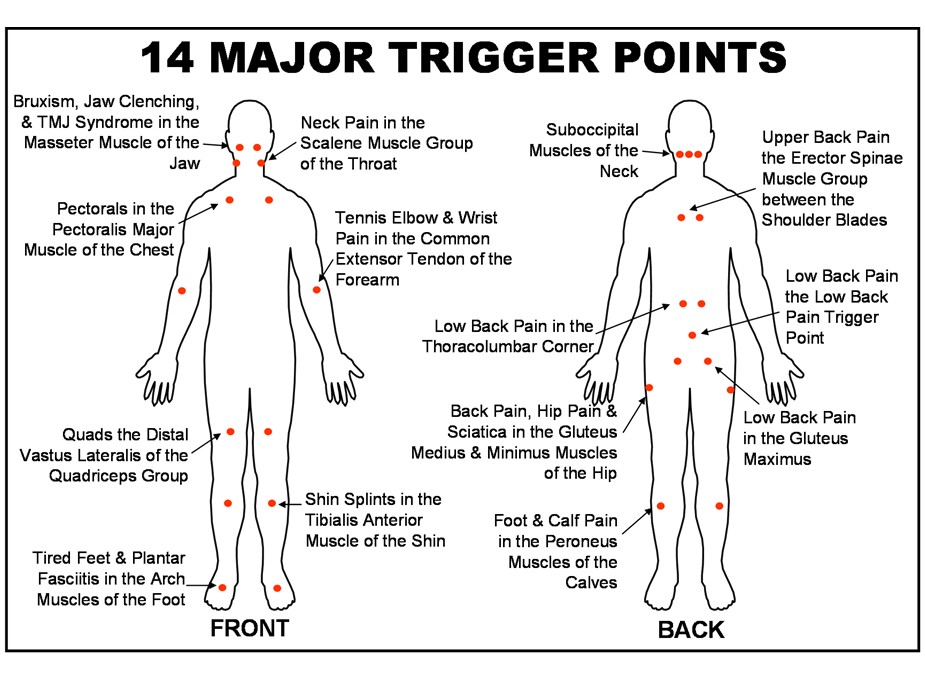

The following sketches illustrate the myofascial syndromes and the reflected or referred pain in anatomical parts of the human body (15):

When searching for active trigger points that are responsible for the patient�s pain, it is important to know the precise location of the pain and to know which specific muscles can refer pain to that location.� Common mechanical factors that can influence many muscles are round-shouldered, head-forward posture, with loss of normal lumbar lordosis, and body assymmetrics including a lower limb length inequality and a small hemi pelvis.� Tightness of the iliopsoas and hamstring muscles can also seriously disrupt balanced posture.� The central nervous system powerfully modulates pain input from muscles in ways that can explain referred or reflected pain and altered sensation from trigger points.� Following table (14) and attached sketches (15) reflect this principle in more detail.

|

Pain Location in the

|

Problems |

Related Muscles

|

|

low back, hip, buttocks (especially immediately under the buttocks), side of the thigh, hamstrings |

sciatica, trochanteric bursitis, low back pain |

gluteus medius and minimus |

|

head, face and neck, but especially the side of the head, behind the ear, the temples and forehead |

headache, neck pain, migraine |

Suboccipital muscles (recti capitis posteriors major and minor, obliqui inferior and superior) |

|

low back, tailbone, lower buttock, abdomen, groin, side of the hip |

low back pain, herniated disc |

Quadratus lumborum, erector spinae |

|

shin, top of the foot, and the big toe |

drop foot, anterior compartment syndrome, medial tibial stress syndrome |

Tibialis anterior |

|

upper back (especially inner edge of the shoulder blade), neck, side of the face, upper chest, shoulder, arm, hand |

Thoracic outlet syndrome, lump in the throat, hoarseness, TMJ syndrome |

Scalenes (anterior, middle, posterior) |

|

elbow, arm, wrist, and hand |

carpal tunnel syndrome, tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis), golfer�s elbow (medial epicondylitis), thoracic outlet syndrome, and several more |

Extensor muscles of the forearm, mobile wad (brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis), extensor digitorum, extensor carpi ulnaris |

|

side of the face, jaw, teeth (rarely) |

bruxism, headache, jaw clenching, TMJ syndrome, toothache, tinnitus |

masseter |

|

lower half of the thigh, knee |

iliotibial band syndrome, patellofemoral pain syndrome |

Quadriceps (vastus lateralis, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, rectus femoris) |

|

chest, upper arm |

�heart attack,� respiratory dysfunction |

Pectoralis major |

|

bottom of the foot |

Plantar fasciitis |

arch muscles |

|

upper back, mainly between the shoulder blades |

scoliosis |

erector spinae muscle group |

|

lower back, buttocks, hip, hamstrings |

low back pain, sciatica, sacroiliac joint dysfunction |

Gluteus maximus |

|

low back, buttocks, hamstrings |

low back pain, sciatica, sacroiliac joint dysfunction |

erector spinae muscle group at L5 |

Trigger Points: Reference List �(Not part of this non-massage techniques online CEU course but provided for information only)

VIDEOS

- Myofascial Trigger Point Finder

- Myofascial Trigger Points Causes and Treatment

- Understanding Trigger Points and Chronic Muscle Pain

- What is a trigger Point and What Causes Them

- Trigger Points and How They Work

- The Gluteus Medius Trigger Points and Low Back Pain

- Muscle and Motion - Anatomy of the Muscular System

- Anterior Trigger Points

- Posterior Trigger Points

- Serratus Posterior Superior Trigger Points

- Scalenes Trigger Points

- Semispinalis Capitis Trigger Points

- Gluteus Maximus Trigger Points

- Gluteus Medius Muscle Quiz

- Gluteus Minimus and Piriformis Trigger Points

- Semitendinosis Trigger Points

- Gluteus Medius Trigger Points

- Triceps Brachii Trigger Points

- Quadratus Lumborum Trigger Points

- Pectineus Trigger Points

- Quadriceps Trigger Points

- Psoas Trigger Points

- Rectus Abdominus Trigger Points

- Soleus Trigger Points

- Peroneus Trigger Points

- Sternocleidomastoid Trigger Points

- Levator Scapulae Trigger Points

- Serratus Anterior

- Trapezius Trigger Points

- Erector Spinae Spinalis Trigger Points

- Gastrocnemius Trigger Points

- Biceps Femoris Trigger Points

ARTICLES

- Biology of trigger points: Bruce Thomson, EasyVigour Project

- Simons: DG: "Myofascial pain syndrome due to trigger points", Chapter 45, Rehabilitation Medicine edited by Joseph GoodGold. C.V. Mosby Co., St. Louis, 1988 (pp 686-723).

- P Brukner, K Khan: Clinical Sports Medicine, Revised Second Edition.

- Clair Davies: Triggerpoint Therapy Workbook - ) Publ. New Harbinger Publications 2001

- Warren Hammer: Neurogenic

Inflammation, or Why a Tennis Elbow Did Not Respond -

http://www.chiroweb.com/archives/23/15/12.html - Shirley A Sahrmann: Diagnosis of and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes Publ. Mosby 2002

- By Gordon Cameron: Is Your

Shoulder Frozen? What Causes The Frozen Shoulder Syndrome?

http://ezinearticles.com/?Is-Your-Shoulder-Frozen?-What-Causes-The-Frozen-Shoulder-Syndrome?&id=17509 - LB Siegel, NJ Cohen, EP Gall:

Adhesive Capsulitis: A Sticky Issue

http://www.aafp.org/afp/990401ap/1843.html - Sandy Simmons: Frozen Shoulder Treatment Tips Page II

http://www.ctds.info/frozen_shoulder_treatment.html - Thomas Janicki: Neurogenic Inflammation in Chronic Pain

Conditions

http://www.pelvicpain.org/pdf/Neurogenic_Inflammation.pdf - Richard K. Bernstein: Frozen Shoulder or Diabetic

Capsulitus

http://www.diabetesincontrol.com/issue189/bernstein.shtml - Michael W. King: Muscle Biochemistry http://web.indstate.edu/thcme/mwking/muscle.html

- D Cross: Trigger Point Diagram Cascade for Diagnosis and Management http://www.pain-education.com/100225.php

- Trigger Points and Myfascial Pain Syndrome, Paul Ingraham

- Trigger Point Workbook

- Two Anatomical Causes of Trigger Points, Alexis Rohlin

TAKE EXAM" or Email minimum 3 page report on Trigger Point Material reviewed to "info@cleanwater4.us" for 12 hour CEU Certificate

Visit www.txmassageceu.com to pay $47 online by using your credit card or paypal a/c for the Trigger Point Theory 12 hour CEU Course